In the roaring era of aviation between the World Wars, a new kind of power transformed the sky. It was not sleek or quiet, but robust, thunderous, and profoundly reliable. This was the era of the radial engine, and its undisputed champion for a generation was the Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp. More than just a piece of machinery, the R-1340 was the beating heart that powered the evolution of commercial air travel, military training, and iconic aircraft from the dusty airmail routes to the combat theaters of World War II.

The History of the R-1340 Wasp

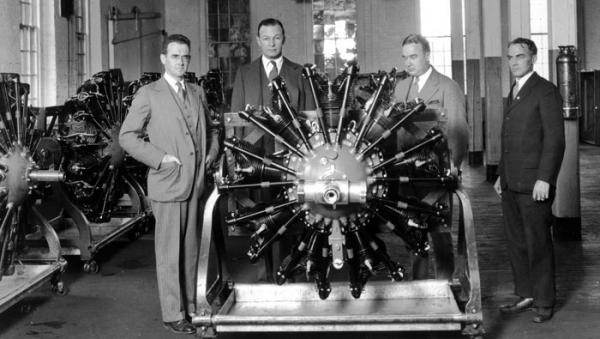

The story begins in the 1920s. The U.S. Navy needed a new, more powerful, and lighter engine for its fighter aircraft. Enter Frederick Rentschler, a former Wright Aeronautical executive, who founded Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in 1925 with a singular vision. His team, including brilliant engineer George Mead, set out to create an engine that would outperform anything else on the market.

In 1926, just one year after the company’s founding, the first Wasp engine completed its qualification test. The results were staggering. The 9-cylinder, air-cooled radial produced 425 horsepower, far more than its contemporaries, while being lighter and more compact. It passed a grueling 150-hour Navy test with flying colors, a testament to its robust engineering from the very beginning.

The “R” stood for radial, and “1340” denoted its displacement in cubic inches (approximately 22 liters). Its immediate success with the Navy was followed by rapid adoption in civilian aviation. It became the engine of choice for trailblazing airliners like the Boeing 247 and the Lockheed Electra, aircraft that made passenger travel faster and more reliable. When World War II erupted, the Wasp found its ultimate calling not in frontline fighters, but as the indispensable trainer engine. It powered the legendary North American AT-6 Texan and the Boeing-Stearman PT-17 Kaydet, teaching a generation of pilots from all Allied nations the fundamentals of flight. Its production was immense, with over 34,000 units built, solidifying its place as one of the most important piston engines in history.

Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Specifications

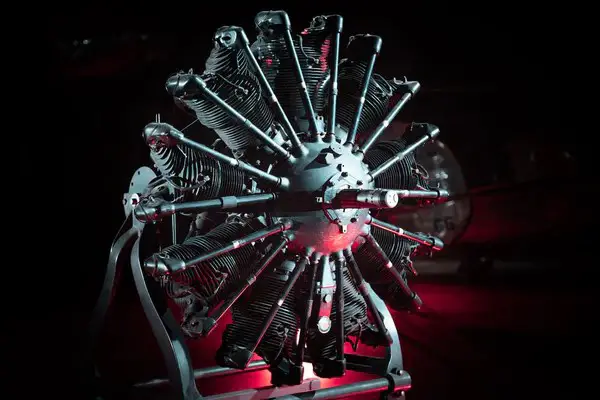

The R-1340’s success was rooted in its elegant and rugged design. It was a masterclass in balancing power, weight, and reliability.

Key Specifications:

- Configuration: 9-cylinder, single-row, air-cooled radial

- Displacement: 1,344 cubic inches (22 liters)

- Bore and Stroke: 5.75 in × 5.5 in (146 mm × 140 mm)

- Dry Weight: Approximately 650 to 750 pounds (295-340 kg), depending on the specific model

- Valvetrain: Two valves per cylinder, operated by pushrods and rocker arms

- Supercharger: Single-speed, single-stage, gear-driven centrifugal supercharger (on most military and high-performance variants)

- Fuel System: Updraft carburetor (early models) or direct fuel injection (later models)

- Power Output: Evolved from 425 hp in 1926 to 600 hp in later wartime variants like the R-1340-AN-1.

The Genius of the Design:

- Air Cooling: By eliminating the need for a heavy liquid cooling system (radiator, coolant, plumbing), the radial design saved tremendous weight and complexity. The engine’s cylinders, with their prominent fins, were exposed directly to the airstream.

- Simplicity and Serviceability: The single-row, 9-cylinder layout was straightforward. Mechanics could access components relatively easily. Its toughness was legendary; it could sustain minor battle damage or rough operation and keep running.

- Supercharging: The integrated supercharger forced air into the cylinders, allowing the engine to maintain its rated power at higher altitudes, a critical feature for military and transport aircraft.

- Robust Construction: Everything about the Wasp was built to last. Its large, slow-turning components (typical rpm was around 2,250 for takeoff) reduced stress and wear, contributing to its famous durability.

What Made the R-1340 Special?

Operating an R-1340 was a visceral, full-sensory experience that modern aviation lacks.

- The Start: Starting a “Wasp” was a ritual. With the prime set, the ignition on, and a call of “Contact!,” the inertia starter (or later electric starter) would engage, slowly grinding the massive crankshaft until a cylinder fired. Then, with a belch of smoke and a sudden, deafening roar, all nine cylinders would erupt to life, shaking the entire airframe.

- The Sound: The engine produced a deep, throaty, and uneven rumble due to the odd number of cylinders firing in sequence. At idle, it had a distinctive “chuckata-chuckata” sound. At full power, it was a glorious, thunderous symphony of raw mechanical power.

- The Feel: In the cockpit, the pilot felt a constant, low-frequency vibration. The smell of burnt aviation gasoline and hot oil permeated the cabin. Managing the engine was a hands-on task: adjusting the mixture control, monitoring cylinder head temperatures, and using the throttle with a deliberate touch.

- The Reliability: Pilots trusted the Wasp. Its wide operating tolerances and simple design meant it was forgiving. It could run lean for economy on long cross-country flights or produce full military power for takeoff and training maneuvers without complaint.

Aircraft Powered by the Wasp

The R-1340’s resume is a roll call of aviation icons:

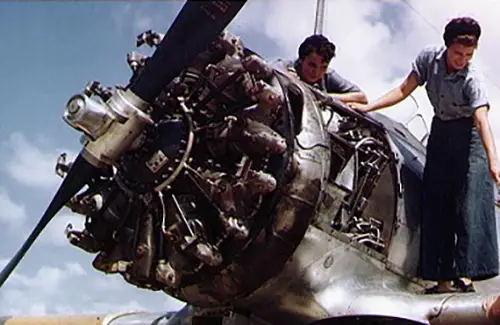

- North American T-6/SNJ Texan: The “Pilot Maker.” This advanced trainer used the Wasp’s reliable power to teach combat pilots formation flying, gunnery, and aerobatics. Its snarl is synonymous with the engine’s sound.

- Boeing-Stearman PT-17/NSN Kaydet: The primary trainer for thousands of U.S. and Allied pilots. The Wasp gave the biplane Stearman the power for basic flight instruction and legendary aerobatic capability.

- Vought F4U Corsair (Early Models): The first prototype Corsairs were powered by the massive twin-row R-2800 Double Wasp, but the XF4U-1 initially flew with an experimental R-1340, proving the airframe before the more powerful engine was ready.

- Commercial Transports: The Boeing 247, often called the first modern airliner, used Wasps. The Lockheed Model 10 Electra, flown by pioneers like Amelia Earhart, also relied on them.

- Utility Workhorses: Countless bush planes, crop dusters, and early helicopters (like the Sikorsky R-4) used the R-1340 for its unshakeable dependability in remote areas.

Owning and Operating a Wasp Today

Today, the R-1340 is a living artifact, primarily found in meticulously restored warbirds and museum pieces. Operating one is a commitment to preserving heritage.

Considerations for Operators:

- Maintenance: Requires specialized mechanics familiar with radial engines. Procedures like “pulling through” the prop to prevent hydraulic lock are essential.

- Parts: While some new parts are manufactured by specialty shops, many components come from salvage or must be meticulously refurbished. The support community among vintage aircraft owners is vital.

- Fuel and Oils: It runs on 100LL avgas, but operators must be vigilant about lead fouling. It consumes significant oil, a characteristic of radial engines where oil lubricates the lower cylinders before being scavenged back to the tank.

- Cost: A major overhaul for an R-1340 can easily cost between $50,000 and $100,000, depending on its condition. It is an investment in history.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it called a “Wasp”?

A: Pratt & Whitney’s tradition was to name its engines after insects or animals known for power or speed (Wasp, Hornet, Twin Wasp). The name “Wasp” evoked something small, powerful, and potent.

Q2: What is the difference between the R-1340 and the R-985 Wasp Jr.?

A: The R-985 Wasp Junior is a smaller, 9-cylinder sibling. With a displacement of 985 cubic inches, it produced between 300-450 hp. It was equally famous, powering aircraft like the Beechcraft Model 18 and the Douglas DC-2.

Q3: How does a radial engine work differently from an inline car engine?

A: In a radial, the cylinders are arranged in a circle around a central crankshaft, like spokes on a wheel. All connecting rods master on a single crankpin. This allows for excellent air-cooling but creates a distinctive wide, round engine shape. An inline engine has cylinders in a row.

Q4: Is the R-1340 still in military service anywhere?

A: Extremely unlikely in an operational military capacity. However, air forces with historical flight demonstration teams (like the USAF or navies with vintage trainers) may operate aircraft with R-1340s for ceremonial purposes.

Q5: What was the engine’s biggest weakness?

A: Its sheer weight and drag were drawbacks for high-performance fighter design, which is why it was superseded by more powerful twin-row radials like the R-1830 and R-2800. Its appetite for oil and fuel was also high by modern standards.

Leave a comment